Saturday, November 21, 2015

Forgeries of Peter Ashley-Russell

It never hurts to educate oneself on forgeries that may be lurking out there, as I know all too well myself (see my blog post on my very own piece of fake Irish silver). So, here is a link to the London Assay Office's publication illustrating Ashley-Russell's "work" including photos of his fake punches and the spoons themselves: http://www.thegoldsmiths.co.uk/media/3751010/ashleyrussell.pdf.

"I Think More": George II Scottish Dessert Spoons

"Je Pense Plus" - "I Think More" - is the motto of the Erskine clan. The three dessert spoons bearing this crest and motto were made in Edinburgh in 1754 by Lothian & Robertson. Thanks to Burke's General Armory, it appears this motto, coupled with the crest of "a dexter hand proper, holding a skene in pale argent, hilted and pommelled or, within a garland of olive leaves proper" is for the Erskine family of Tinwald, County Dumfries (320). I believe Charles Erskine (or Areskine) had these spoons made. Charles Erksine, born in 1680, married Grizel Grierson in 1712, heiress of John

Grierson of Barjarg, through whom he acquired the lands of Barjarg in

Dumfriesshire. In August of 1753, he married again to Elizabeth, daughter of William Harestanes of Craigs in Kirkcudbright. Perhaps Elizabeth had these dessert spoons made shortly after her marriage to Charles. It is also possible that Charles' son James had these spoons made when he was nominated as one of the Barons of the Court of Exchequer in May 1754. I am choosing, however, to focus on Charles Erskine in this article. Below is a portrait of Charles Erskine

|

| Photo credit: National Galleries of Scotland |

Charles Ereskine was the third son of Sir Charles Erskine of Alva, baronet, and great-grandson of John Erskine, Earl of Mar and treasurer of Scotland. Charles Erskine had a successful legal career. In 1700, at the age of 20, Charles Erskine became one of the four regents of Edinburgh University, and in 1707, he became the first professor of public of Law of Nature and Nations at the university. Following his appointment, he left to study the law in Leiden in the Netherlands (Cairns 334). He was appointed Solicitor General for Scotland in 1725, served as Lord Advocate between 1737 and 1742, and was Lord Justice Clerk - the second most senior judge in Scotland - from 1748 until his death in 1763. In 1744, Charles Erskine was raised to the supreme criminal and civil courts as Lord Tinwald. Below is a photograph of Tinwald House in Dumfriesshire, built in 1740 and designed by architect William Adam. Charles Erskine later sold his estates at Tinwald to purchase the family estate of Alva from his nephew, Sir Henry Erskine (345):

|

| © Copyright Colin Kinnear and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence |

As a lawyer, intellectual, linguist, traveler, a patron of the arts and a book collector, Charles Erskine was in the thick of the Scottish Enlightenment (Baston 1). He was one of the founding members of the Edinburgh Philosophical Society in 1737, a member of the Society of Improvers in the Knowledge of Agriculture, a member of the Board of Trustees for Fisheries and Manufactures, and an extraordinary Director of the Royal Bank of Scotland (Cairns 345). Charles Erskine was described by a contemporary as "not only an eminent lawyer and judge, but likewise a polite scholar, and an elegant speaker and writer" (346).

Following are photographs of the spoons and their hallmarks:

Sources:

Baston, Karen Grudzien. "The Library of Charles Areskine (1680-1763): Book Collecting and Lawyers in Scotland, 1700-1760." The Early Modern Intelligencer. WordPress, 2010.

Web. 21 Nov. 2015.

Burke, Bernard. The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales: Comprising & Registry of Armorial Bearings from the Earliest to the Present Time. Harrison & Sons,

1864. Google Books. Web. 15 Nov. 2015.

Cairns, John. "The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: The Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair." Edinburgh Law Review, Vol 11, No. 3, pp. 300-48, 2007. Web. 21 Nov. 2015. DOI:

10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300.

Straiton, Doug. "Charles (Erskine) Areskine (1680-1763)." WikiTree. Interesting.com, Inc. 23 Jan. 2015. Web. 21 Nov. 2015.

Wikipedia contributors. "Charles Erskine, Lord Tinwald." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 4 May. 2015. Web. 15 Nov. 2015.

Wikipedia contributors. "Tinwald House." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 10 Oct. 2015. Web. 15 Nov. 2015.

Wikipedia contributors. "Charles Erskine, Lord Tinwald." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 4 May. 2015. Web. 15 Nov. 2015.

Saturday, November 14, 2015

Theta Charity Anitques Show, Houston, Texas

Sometimes you need to spend 15 minutes expounding on the beauty of a flared foot on an early Scottish silver mug. Sometimes you simply need to clutch a Paul de Lamerie dinner plate to your chest as you look at the dealer's other silver. Sometimes you just need to listen to someone talk about their collecting passion even though it may not be your own. And sometimes, you need to try on a 4-carat Van Cleef and Arpels diamond ring. I got to do all of these things and more at the Theta Charity Antiques show in Houston yesterday.

The early Scottish mug was at Shrubsole. After having looked at items on their website and in their catalogues for so long, it was a whole new experience getting to see them in the flesh. Benjamin Miller, Director of Research at Shrubsole, was a lot of fun and indulged my need to hold and discuss several pieces of silver with great enthusiasm. At one point, he put a ginormous square salver by Paul de Lamerie in my hands which could easily replace dumbells for a bicep workout. Poor man had a lot of polishing to do after I left. I was excited to also meet Tim Martin, who was just as personable in person as he is in his emails. One day soon I will have to visit their shop in New York for more silver fondling and discussion.

I found the Paul de Lamerie dinner plate at a dealer previously unknown to me, The Silver Vault out of Woodstock, Illinois. The shop does not have a web presence, so I cannot point you to a website. I quickly saw that Peter Tinkler, one of the owners, shared my enthusiasm and passion for good, old, plain silver and we spent quite a while talking. Peter's father Rod was also on hand to discuss, among other topics, his thoughts on feminine versus masculine silver and training chickens by whistling, and calling him an absolutely delightful man would be scant praise indeed. I don't know the last time - if ever - that I have laughed so much when talking about silver. The dinner plate was made in 1725 and is number 20 in a large set made by de Lamerie for Benjamin Mildmay when he was 19th Baron Fitzwalter. Mildmay was created Earl Fitzwalter in 1730, and two previous posts of mine - here and here - discuss the inventory of his plate taken in 1739 and work de Lamerie did for him. The Clark Art Institute has a set of twelve plates by de Lamerie of 1725 from the same set as the Silver Vault plate. The Fitzwalter plate inventory contains the following entry, and one assumes it must include the 1725 dinner plates:

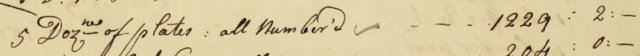

Paul de Lamerie's work ledgers for Mildmay contain an entry for "To 12 Dishes & 3 Dozen of plates" with entries for the fashioning and engraving of same. Although the work on the page containing these entries is not dated, the first date on the following page is December 5, 1727, so we can assume the three dozen plates were made prior to this date. The highest plate number in the Clark Art Institute collection is No. 33, so it is likely these plates and the Silver Vault plate are part of the "3 Dozen of plates" listed in de Lamerie's ledger:

I also had the pleasure of meeting Mary Wise of Grosvenor Antiques, a dealer in antique porcelain. Although I am not a collector of early English porcelain, I could appreciate the beautiful pieces she had and it was fun to see forms that I am familiar with in silver. Mary truly has a passion for early porcelain, and her knowledge of her preferred subject was inspiring.

Then, drawn in by the amiability and invitation of dealers Steven Fearnley and David McKeone of J.S. Fearnley to try on jewellery for fun, I tried on a gorgeous cushion-cut diamond ring, an old stone in a newer setting by Van Cleef and Arpels. And it fit. Again, Steven was so willing to talk with us and tell us about his pieces.

We had heard about the show from wonderful local dealers of antique jewellery, Bell and Bird, and when we received unsolicited tickets in the mail from Tim Martin, that clinched it. To meet, talk with, bounce ideas off others who share a passion for antiques is so invigorating, and when it's your area of collecting, so much the better. Every dealer we spoke with was enthusiastic and genuinely happy to share their knowledge with us. Thank you to the dealers at the Theta Charity Antiques Show for a wonderful time.

Tuesday, July 14, 2015

Earl Fitzwalter's Bottle Tickets

Paul de Lamerie's ledger recording the work he did for Earl Fitzwalter has an interesting entry:

"To mending & added Silver to 3 pieces with Chains to hang on Bottles of Wine." That description sounds an awful lot like a wine label or bottle ticket. So why not just identify it by one of those names?

The ledger entry is dated March 21, 1737 - which I believe is a Julian calendar date - so, if I have my calculations correct, March 21, 1737 in the Julian calendar corresponds to April 1, 1738 in the Gregorian calendar. According to the Google Books entry for the book Wine Labels, 1730- 2003: a Worldwide History by John Salter, "silver wine labels first made their appearance in the 1730s to identify the contents of unmarked opaque glass wine bottles." N.M. Penzer, in his The Book of the Wine-Label, discusses the Plate Offenses Act of 1738, which set forth the mandatory marks to be applied to plate and included an extensive list of items by name or by characteristic not required to be so marked (34-35). As there is no mention of wine labels or bottle tickets in this list, Mr. Penzer concludes that these items were unknown at this time (35). What I believe Mr. Penzer to be saying is that, had bottle tickets been common when this Act was written, in his opinion by reason of their smallness and lightness they would not have been required to be hallmarked, and therefore should have appeared by name in the exempt list along with the other specifically-identified items of plate "connected with the bottle." (Id.).

Unfortunately, I do not have access to a copy of the Wine Labels book to read about or see photographs of these earliest silver wine labels. What Paul de Lamerie's ledger entry tells me, however, is that in early 1738, bottle tickets - by any name - were likely not very well known, otherwise Lamerie (or his ledger-keeper) would have used that name instead of the description of the item, e.g. "To mending and added silver to three bottle tickets." This entry is for a repair, so we also know that the Earl's bottle tickets were made prior to 1738. It's too bad we don't know exactly when, or by whom, they were made. So, although not completely unknown in 1738, it would seem bottle tickets were sufficiently uncommon for a prominent maker not to be able to record them by name.

Sources:

Essex Records Office: Estate and Family Records, D/DM F13.

Penzer, N.M. The Book of the Wine-Label. London: Home & Van Thal, 1947. Internet Archive. Web, 10 July 2015.

Sources:

Essex Records Office: Estate and Family Records, D/DM F13.

Penzer, N.M. The Book of the Wine-Label. London: Home & Van Thal, 1947. Internet Archive. Web, 10 July 2015.

Tuesday, July 7, 2015

Earl Fitzwalter's Salt Spoons

Recently I purchased a copy of the inventory of the Earl of Fitzwalter's plate taken by his butler, Henry Longmore, on June 22, 1739 from the Essex Records Office. Among the entries for five dozen plates, the dozens of "forck's" and several candlesticks, is an entry for "4 wrought Salts Spoons" weighing 2 oz 6 dwts, or 71.5 grams. I tend to think of salt spoons along the lines of Geoffrey Wills's definition in Silver: early 18th century examples that are miniatures of ordinary spoons (130), which would not seem to distinguish them much from snuff spoons. In a previous post called Snuff Spoons or Early Salt Spoons, I asked just that question: could the small spoons we call snuff spoons also be early salt spoons?

Below is a photograph of four small spoons in my silver drawer. The smallest one is 3 1/8 inches and the largest is 3 5/16 inches. Two of these spoons are "heavy" for their size, but are only about 9 grams each. The four salt spoons in the Fitzwalter inventory weigh in at almost 17.9 grams apiece. Those seem to be some pretty heavy salt spoons.

Below is an excerpt from Longmore's inventory showing the entry for the Salts Spoons. Note also the listing for the mustard spoon weighing 9 pennyweights, or 14 grams.

Does anyone know of any early Irish salt/snuff spoons? Along with early Irish rattail teaspoons, I have not seen any early Irish salt/snuff spoons. Early Irish salt trenchers exist (see the photographs in my previous post on my visit to the San Antonio Museum of Art) - though I don't see nearly as many as English examples - so one would assume that early Irish salt spoons also existed at one time. Same for early Irish rattail teaspoons: there are early Irish tea pots, leading one to believe that teaspoons were made early on, as well.

Sources:

Essex Records Office: Estate and Family Records, D/DM F12.

Wills, Geoffrey. Silver: for pleasure and investment. New York: Arco Publishing Company, Inc., 1969. Print.

Wednesday, April 1, 2015

George III Irish Silver Bowl - *GASP* It's a FAKE!

~Below is my original post on the bowl. After posting it, I received a nice note from a reader letting me know this bowl is a fake. At the end of this post is more information on the faker~

Below is an Irish silver bowl that dates to 1798 in the reign of George III. Although the bowl is later than I normally collect, it reminds me of earlier forms. It measures 4 1/8 inches in diameter (10.5 cm) and 2 3/8 inches (6 cm) in height, is of heavy gauge, and is plain with a lovely hammered finish.

|

| Strawberries. Yum. |

The maker's mark on the bowl is IE surrounded by pellets. Unfortunately, I haven't been able to attribute this mark to a silversmith. The only Dublin maker's mark of IE referenced by Douglas Bennett that fits the date of the bowl is James England, who worked from 1791-1815 (167). However, James England's punch is not surrounded by pellets.

Does anyone have an idea who this maker is?

I believe this would have been used as a sugar bowl. Or could it have been a waste bowl?

|

| Hallmarks on bowl |

UPDATE: IT'S A FAKE!! After a tipster let me know this bowl was a fake, I have to admit I was a bit disappointed, but I also had this thought: "I thought it was not quite right!". I like the bowl, it was not expensive, but before and after buying it, something about it nagged me. It didn't seem to fit the design of sugar bowls of the 1790s in Ireland. However, I brushed away the nagging feeling and bought it anyway without doing as much research as I should have.

A friend of mine reminded me that this faker is dealt with by Bennett in his Collecting Irish Silver. About the faker, Bennett has this to say: "'IE' is well known to both the London and Dublin assay offices, where examples of his work are kept for reference. (Do they want mine?) Many an antique dealer has been caught out with these marks, and the only clue that can be offered is to watch out for the distinctive maker's mark of 'IE' with small beads encircling the initials" (242).

Distinctive maker's mark, indeed. Has anyone else fallen into IE's trap?

Bennett, Douglas. Collecting Irish Silver. London: Souvenir Press Ltd., 1984. Print.

Tuesday, March 17, 2015

Visit to the Irish Silver at the San Antonio Museum of Art

Recently I made my annual birthday pilgrimage to see the fantastic collection of Irish silver at the San Antonio Museum of Art. I usually find myself alone in the silver room, so I can take my time going from case to case, talking to myself and pressing my nose against the display cases. Though I have visited this collection several times, the joy and awe and excitement I feel on seeing the silver is never diminished. There are just so many darn good pieces to look at.

While the silver itself is stunning, the way it is displayed could be more so. Drawbacks include poor lighting; all of the natural light has been blocked out and the overhead bulbs seem to be aimed on some pieces at the worst angle possible. There is crackling and waving to the plexiglass of one display case in particular (where the 17th century slip top spoon resides) which distorts the objects in the case. And, the pieces would benefit greatly from a polish (for which I eagerly volunteer my services!). The silver could also be more imaginatively displayed. For instance, since there are four matching salts made by John Hamilton, at least one of the salts could be displayed to enable the viewer to see the hallmarks. Same for the pair of salts by Henry Daniel. Using mirrors and magnifiers would also allow visitors to see hallmarks and engraving. Negatives aside, Mr. Rowan's collection of Irish silver was once again an absolute joy to visit.

While the silver itself is stunning, the way it is displayed could be more so. Drawbacks include poor lighting; all of the natural light has been blocked out and the overhead bulbs seem to be aimed on some pieces at the worst angle possible. There is crackling and waving to the plexiglass of one display case in particular (where the 17th century slip top spoon resides) which distorts the objects in the case. And, the pieces would benefit greatly from a polish (for which I eagerly volunteer my services!). The silver could also be more imaginatively displayed. For instance, since there are four matching salts made by John Hamilton, at least one of the salts could be displayed to enable the viewer to see the hallmarks. Same for the pair of salts by Henry Daniel. Using mirrors and magnifiers would also allow visitors to see hallmarks and engraving. Negatives aside, Mr. Rowan's collection of Irish silver was once again an absolute joy to visit.

Unlike my visit there this time last year, I remembered to take some photographs, though not by any means very good photographs. I hope you enjoy looking at them.

|

| Clockwise from upper left: Chocolate pot by David King, c. 1713; Set of three casters by Thomas Bolton, 1708/09; Slip top spoon, 1655/56; Pair of tapersticks by Thomas Bolton, c. 1710 |

|

| Clockwise from upper left: Herb or small teapot, Matthew West, c. 1775; Covered sugar bowl by Peter Racine, 1736/37; Teapot by Bartholomew Mosse 1736/37; Covered cream jug by William Homer, c. 1760 |

|

| Two pairs of salts by John Hamilton, c. 1730; One of a pair of salts by Henry Daniel, 1715/16; Dressing table box by Joseph Walker, 1717/18; Pair of toilet boxes by Thomas Bolton, 1699/1700 |

| |||

| Top: Selection of freedom boxes. Bottom: Box with pair of tea canisters and sugar box by Ambrose Boxwell, c. 1770 |

Thursday, February 26, 2015

Francis Warren Bonham and his Plate

|

| Miniature of Francis Warren Bonham, blogger's collection |

Francis Warren Bonham was born in 1740 in Ballintaggart, County Kildare, Ireland. He attended Trinity College in Dublin where school records show he was one of the socii comitates, or fellow commoners, which meant he paid twice the normal fees for tuition and room and board, but could finish his studies in three years instead of four. Francis Warren Bonham graduated on July 15, 1756 and was called to the Irish bar in 1764. On January 23, 1766, he was elected a member of the Royal Dublin Society. The following year, Bonham married Mary Ann Leslie, daughter of James Leslie, Bishop of Limerick, and together they had one son (John) and one daughter (Joyce). In 1776, he married again to Dorothea Herbert of Muckross, with whom he had five more children, only two of whom lived to adulthood, a son Francis Robert and a daughter Susanna. Bonham inherited the family property in County Kildare in 1781, but he moved to England before the end of the century. In 1808, when he made his will, Bonham stated he was "late of the City of Dublin but now of the City of Bath." He died in Richmond, Surrey on September 8, 1810.

Following is an excerpt from Francis Warren Bonham's last will and testament:

"I give such articles of plate as have the mark or crest of the thistle or any other mark crest or arms than those of the mark crest or arms of my own family unto my said son John Bonham...I give to my said daughter Susanna Bonham my two two-handled silver cups with my arms and crest thereto and as to all other my plate...I give...unto my said son Francis Robert Bonham."

The thistle is the crest of the Leslie family of Ireland, of whom Bonham's first wife Mary Ann was a part, so he leaves all his plate with this crest to their son John. I would assume that most of the silver Bonham leaves his heirs is Irish. What forms did the silver with the Leslie crest take that he left to his son John? Do the two-handled cups with the Bonham arms and crest survive?

Sources:

Burke, Ashworth Peter. Family Records. Harrison, 1897. Google Books. Web. 18 Feb. 2015

Burtchaell, George Dames and Thomas Ulick Sadleir. "A Register of the Students, Graduates, Professors, and Provosts of Trinity College, in the University of Dublin."

Ireland Genealogy Projects Archives, n.d. Web. 18 Feb. 2015.

Fisher, David R. "BONHAM, Francis Robert." The History of Parliament.. Institute of Historical Research, n.d. Web. 18 Feb. 2015.

"Past Members: Francis Warren Bonham." RDS. RDS Foundation Programme, n.d. Web. 18 Feb. 2015.

The National Archives: PROB 11/1515

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

Snuff Spoons or Early Salt Spoons?

Geoffrey Wills, in his book Silver: for pleasure and investment, has this to say about salt spoons: "[E]arly eighteenth century examples are miniatures of ordinary spoons. They were followed by some in the shape of a ladle and others with a bowl in the form of a shovel." He goes on to say the following about snuff spoons: "[M]iniatures of ordinary spoons were made during the eighteenth century for keeping inside a box to assist in taking snuff" (130).

I recently found two small rattail spoons, pictured below.

|

| Left to right: Spoon by Andrew Archer and spoon by John Ladyman |

|

| Top to bottom: Comparison of Ladyman marks on snuff spoon (left) and tablespoon (right); Archer marks. Can you make out the lion's head erased? |

|

| Size comparison of spoons, left to right: Archer snuff spoon, Ladyman snuff spoon, Ladyman teaspoon, Ladyman tablespoon |

The first, by Andrew Archer, is 3 1/8 inches long and, if I squint my eyes just right, the second mark looks like the lion's head erased. For its size it has a good gauge. The second spoon is just over 3 1/4 inches in length and is made by John Ladyman. The complete maker's mark is not present, but comparing it to other pieces in my collection with his mark, I feel confident attributing it to Ladyman. The lion's head erased is clear.

So, are these snuff spoons or early 18th century salt spoons?

Sources:

Wills, Geoffrey. Silver: for pleasure and investment. New York: Arco Publishing Company, Inc., 1969. Print.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)