Saturday, November 21, 2015

Forgeries of Peter Ashley-Russell

It never hurts to educate oneself on forgeries that may be lurking out there, as I know all too well myself (see my blog post on my very own piece of fake Irish silver). So, here is a link to the London Assay Office's publication illustrating Ashley-Russell's "work" including photos of his fake punches and the spoons themselves: http://www.thegoldsmiths.co.uk/media/3751010/ashleyrussell.pdf.

"I Think More": George II Scottish Dessert Spoons

"Je Pense Plus" - "I Think More" - is the motto of the Erskine clan. The three dessert spoons bearing this crest and motto were made in Edinburgh in 1754 by Lothian & Robertson. Thanks to Burke's General Armory, it appears this motto, coupled with the crest of "a dexter hand proper, holding a skene in pale argent, hilted and pommelled or, within a garland of olive leaves proper" is for the Erskine family of Tinwald, County Dumfries (320). I believe Charles Erskine (or Areskine) had these spoons made. Charles Erksine, born in 1680, married Grizel Grierson in 1712, heiress of John

Grierson of Barjarg, through whom he acquired the lands of Barjarg in

Dumfriesshire. In August of 1753, he married again to Elizabeth, daughter of William Harestanes of Craigs in Kirkcudbright. Perhaps Elizabeth had these dessert spoons made shortly after her marriage to Charles. It is also possible that Charles' son James had these spoons made when he was nominated as one of the Barons of the Court of Exchequer in May 1754. I am choosing, however, to focus on Charles Erskine in this article. Below is a portrait of Charles Erskine

|

| Photo credit: National Galleries of Scotland |

Charles Ereskine was the third son of Sir Charles Erskine of Alva, baronet, and great-grandson of John Erskine, Earl of Mar and treasurer of Scotland. Charles Erskine had a successful legal career. In 1700, at the age of 20, Charles Erskine became one of the four regents of Edinburgh University, and in 1707, he became the first professor of public of Law of Nature and Nations at the university. Following his appointment, he left to study the law in Leiden in the Netherlands (Cairns 334). He was appointed Solicitor General for Scotland in 1725, served as Lord Advocate between 1737 and 1742, and was Lord Justice Clerk - the second most senior judge in Scotland - from 1748 until his death in 1763. In 1744, Charles Erskine was raised to the supreme criminal and civil courts as Lord Tinwald. Below is a photograph of Tinwald House in Dumfriesshire, built in 1740 and designed by architect William Adam. Charles Erskine later sold his estates at Tinwald to purchase the family estate of Alva from his nephew, Sir Henry Erskine (345):

|

| © Copyright Colin Kinnear and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence |

As a lawyer, intellectual, linguist, traveler, a patron of the arts and a book collector, Charles Erskine was in the thick of the Scottish Enlightenment (Baston 1). He was one of the founding members of the Edinburgh Philosophical Society in 1737, a member of the Society of Improvers in the Knowledge of Agriculture, a member of the Board of Trustees for Fisheries and Manufactures, and an extraordinary Director of the Royal Bank of Scotland (Cairns 345). Charles Erskine was described by a contemporary as "not only an eminent lawyer and judge, but likewise a polite scholar, and an elegant speaker and writer" (346).

Following are photographs of the spoons and their hallmarks:

Sources:

Baston, Karen Grudzien. "The Library of Charles Areskine (1680-1763): Book Collecting and Lawyers in Scotland, 1700-1760." The Early Modern Intelligencer. WordPress, 2010.

Web. 21 Nov. 2015.

Burke, Bernard. The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales: Comprising & Registry of Armorial Bearings from the Earliest to the Present Time. Harrison & Sons,

1864. Google Books. Web. 15 Nov. 2015.

Cairns, John. "The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: The Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair." Edinburgh Law Review, Vol 11, No. 3, pp. 300-48, 2007. Web. 21 Nov. 2015. DOI:

10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300.

Straiton, Doug. "Charles (Erskine) Areskine (1680-1763)." WikiTree. Interesting.com, Inc. 23 Jan. 2015. Web. 21 Nov. 2015.

Wikipedia contributors. "Charles Erskine, Lord Tinwald." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 4 May. 2015. Web. 15 Nov. 2015.

Wikipedia contributors. "Tinwald House." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 10 Oct. 2015. Web. 15 Nov. 2015.

Wikipedia contributors. "Charles Erskine, Lord Tinwald." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 4 May. 2015. Web. 15 Nov. 2015.

Saturday, November 14, 2015

Theta Charity Anitques Show, Houston, Texas

Sometimes you need to spend 15 minutes expounding on the beauty of a flared foot on an early Scottish silver mug. Sometimes you simply need to clutch a Paul de Lamerie dinner plate to your chest as you look at the dealer's other silver. Sometimes you just need to listen to someone talk about their collecting passion even though it may not be your own. And sometimes, you need to try on a 4-carat Van Cleef and Arpels diamond ring. I got to do all of these things and more at the Theta Charity Antiques show in Houston yesterday.

The early Scottish mug was at Shrubsole. After having looked at items on their website and in their catalogues for so long, it was a whole new experience getting to see them in the flesh. Benjamin Miller, Director of Research at Shrubsole, was a lot of fun and indulged my need to hold and discuss several pieces of silver with great enthusiasm. At one point, he put a ginormous square salver by Paul de Lamerie in my hands which could easily replace dumbells for a bicep workout. Poor man had a lot of polishing to do after I left. I was excited to also meet Tim Martin, who was just as personable in person as he is in his emails. One day soon I will have to visit their shop in New York for more silver fondling and discussion.

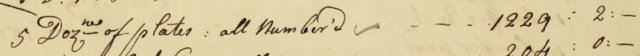

I found the Paul de Lamerie dinner plate at a dealer previously unknown to me, The Silver Vault out of Woodstock, Illinois. The shop does not have a web presence, so I cannot point you to a website. I quickly saw that Peter Tinkler, one of the owners, shared my enthusiasm and passion for good, old, plain silver and we spent quite a while talking. Peter's father Rod was also on hand to discuss, among other topics, his thoughts on feminine versus masculine silver and training chickens by whistling, and calling him an absolutely delightful man would be scant praise indeed. I don't know the last time - if ever - that I have laughed so much when talking about silver. The dinner plate was made in 1725 and is number 20 in a large set made by de Lamerie for Benjamin Mildmay when he was 19th Baron Fitzwalter. Mildmay was created Earl Fitzwalter in 1730, and two previous posts of mine - here and here - discuss the inventory of his plate taken in 1739 and work de Lamerie did for him. The Clark Art Institute has a set of twelve plates by de Lamerie of 1725 from the same set as the Silver Vault plate. The Fitzwalter plate inventory contains the following entry, and one assumes it must include the 1725 dinner plates:

Paul de Lamerie's work ledgers for Mildmay contain an entry for "To 12 Dishes & 3 Dozen of plates" with entries for the fashioning and engraving of same. Although the work on the page containing these entries is not dated, the first date on the following page is December 5, 1727, so we can assume the three dozen plates were made prior to this date. The highest plate number in the Clark Art Institute collection is No. 33, so it is likely these plates and the Silver Vault plate are part of the "3 Dozen of plates" listed in de Lamerie's ledger:

I also had the pleasure of meeting Mary Wise of Grosvenor Antiques, a dealer in antique porcelain. Although I am not a collector of early English porcelain, I could appreciate the beautiful pieces she had and it was fun to see forms that I am familiar with in silver. Mary truly has a passion for early porcelain, and her knowledge of her preferred subject was inspiring.

Then, drawn in by the amiability and invitation of dealers Steven Fearnley and David McKeone of J.S. Fearnley to try on jewellery for fun, I tried on a gorgeous cushion-cut diamond ring, an old stone in a newer setting by Van Cleef and Arpels. And it fit. Again, Steven was so willing to talk with us and tell us about his pieces.

We had heard about the show from wonderful local dealers of antique jewellery, Bell and Bird, and when we received unsolicited tickets in the mail from Tim Martin, that clinched it. To meet, talk with, bounce ideas off others who share a passion for antiques is so invigorating, and when it's your area of collecting, so much the better. Every dealer we spoke with was enthusiastic and genuinely happy to share their knowledge with us. Thank you to the dealers at the Theta Charity Antiques Show for a wonderful time.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)